On August 5, 2025, a federal judge ruled that the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service violated the Endangered Species Act by wrongly denying protections for Northern Rocky Mountain gray wolves. The ruling calls for a review of their status—a process that could restore critical safeguards—but hunting groups quickly filed an appeal, stalling federal review and delaying potential protections.

Background: Northern Rocky Mountains DPS

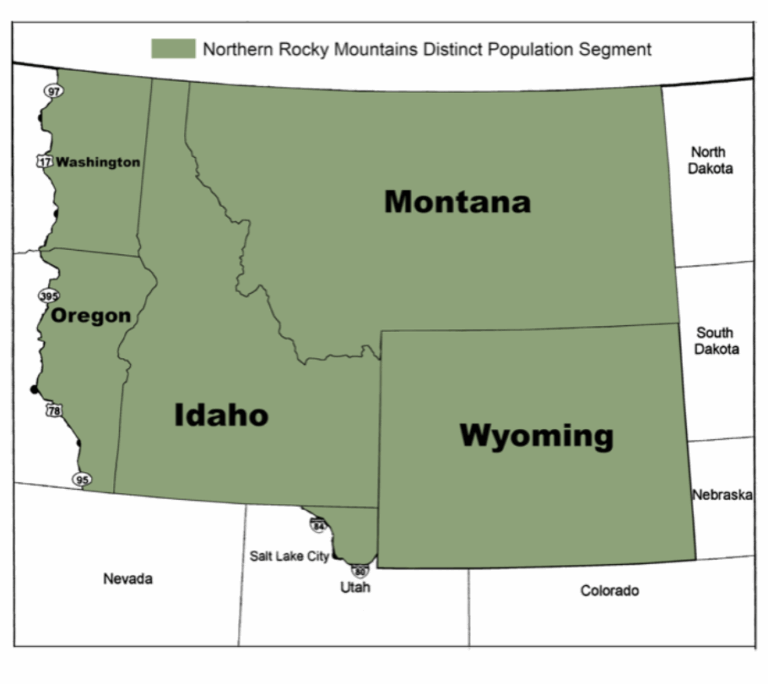

In 2009, wolves in Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, the eastern third of Oregon and Washington, and a small part of northern Utah were designated as the Northern Rocky Mountains Distinct Population Segment (NRM DPS). See map. Two years later, in 2011, wolves in the NRM DPS lost federal protections when a congressional rider, introduced by Rep. Mike Simpson (R-ID) and Sen. Jon Tester (D-MT), was attached to a must-pass federal budget bill and forced their removal from the endangered species list.

Every year, Congress must pass budget bills to fund government agencies. Hidden in these massive spending bills are often “riders,” or amendments unrelated to the budget, slipped in to advance controversial policies that are unlikely to pass on their own.

This was the first and only time Congress has overridden the authority of the USFWS and legislatively delisted a species.

Since then, wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountains Distinct Population Segment have been under state management. States like Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming have adopted aggressive wolf-killing policies, including unlimited tag purchases, year-round seasons, night hunting, aerial gunning, and bounty-style reimbursement programs, all designed to drastically reduce wolf numbers.

Gray Wolves Caught Between State and Federal Management

On October 29, 2020, under the Trump Administration, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) finalized a rule removing Endangered Species Act (ESA) protections for all gray wolves in the Lower 48, except for Mexican gray wolves in the Southwest. Management shifted to state and tribal agencies, with USFWS committing to five years of monitoring. Yet in states hostile to wolves, the species quickly came under intense hunting pressure.

In Wisconsin, for example, state law mandates wolf hunts whenever wolves are not federally protected. Following delisting in 2020, Wisconsin held a seven-day public wolf hunt on February 22, 2021 with a quota of 119 wolves for licensed hunters and 81 for Native American tribes.

In just three days, hunters killed 218 wolves, nearly 100 over the quota and about 22% of the state’s wolf population, forcing an early closure. The intensity and high toll of the hunt drew widespread criticism, and set the stage for renewed legal battles over whether states could responsibly manage wolf populations.

Although President Biden’s Executive Order 13990 required review of Trump-era rules, the 2020 delisting of gray wolves was ultimately upheld on January 4, 2021. Shortly after, several conservation groups filed a lawsuit challenging the decision.

On February 10, 2022, U.S. District Court Judge Jeffrey White overturned the 2020 rule restoring federal protections for gray wolves outside the Northern Rockies. He found that the USFWS relied on only two wolf populations to justify nationwide delisting, failed to apply the “significant portion of its range” standard, and ignored the loss of the species’ historic range. To follow the court’s order, the agency issued a final rule on November 2, 2023, restoring protections to gray wolves in the Lower 48 outside of the Northern Rockies. Under this rule, wolves were listed as threatened in Minnesota and endangered across the remainder of the Lower 48.

The Biden Administration appealed the district court’s decision on September 13, 2024, arguing that the Endangered Species Act’s goal is to prevent extinction, not necessarily to restore animals to their full historic range. The appeal is still pending before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Petitions for Northern Rockies Wolves

Because the 2023 relisting excluded wolves of the Northern Rockies, as they had already lost protections through a congressional rider in 2011, conservation groups pushed for their protection. In late May, 2021, they filed an emergency petition asking the USFWS to relist wolves as either threatened or endangered in the NRM DPS or in a broader “Western DPS” that would include the Northern Rockies, West Coast, and Southern Rockies. Two months later, a second petition followed, seeking endangered status for a Western population segment covering Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, Oregon, Washington, Colorado, California, Nevada, and northern Arizona.

By mid-September 2021, the USFWS published a 90-day finding that both petitions presented enough information to warrant a 12-month review. The agency’s Species Status Assessment looked at gray wolves in California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming; and portions of Arizona and New Mexico. See map.

After the agency missed its June 1, 2022 deadline, conservationists filed a lawsuit against the Department of Interior two months later. A settlement was reached in early 2023 that required the USFWS to publish a 12-month finding by February 2, 2024.

USFWS “Not Warranted” Finding

After taking more than two years, the USFWS issued a ‘not warranted’ finding on February 2, 2024, following a lawsuit that required the agency to comply with the Endangered Species Act. The agency concluded that wolves in the Northern Rockies are part of the larger Western U.S. wolf population and do not qualify as a separate population for listing. The decision did not change the endangered status of wolves in states like California, Oregon, and Washington, since any revision there would require a new rule. At the same time, USFWS announced it will develop a national wolf recovery plan by December 12, 2025.

Judge Rules USFWS Violated ESA

The February 2024 “not warranted” decision led to two new lawsuits filed in early April by coalitions of conservation groups. The groups argued that wolf management policies in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, which sought to reduce population numbers to the lowest levels allowed, demonstrated the inadequacy of existing state regulations to ensure wolves’ long-term survival. They also contended that the agency failed to consider wolves across a ‘significant portion’ of their range by discounting historical habitat, Colorado, and the West Coast, and ignored the best available science on population dynamics and human-caused mortality.

On August 5, 2025, U.S. District Judge Donald Molloy ruled that USFWS had wrongly denied federal protections for wolves in the Northern Rockies. While the court agreed that the Northern Rocky Mountains do not qualify as a distinct population segment, it found that the broader Western U.S. population does. The Judge also determined that the agency failed to properly weigh the best available science and the cumulative impacts of aggressive state management on wolf recovery. Molloy further emphasized that the Endangered Species Act requires the agency to consider the Southern Rockies—including most of Utah, northern New Mexico, northern Arizona, and Colorado—where wolves are returning through natural dispersal and reintroduction programs.

Judge Molloy’s ruling did not immediately change the status of wolves in the Northern Rockies. However, it ordered the USFWS to reconsider whether they should receive federal protection, a process that could lead to restored safeguards and increased oversight in states where wolves remain under heavy pressure.

Challenges Continue After Court Ruling

On August 6, 2025, just one day after the ruling, three hunting organizations filed a joint notice of appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. This appeal allows the USFWS to delay reconsidering the status of wolves in the Northern Rockies while the case moves through the courts. It also raises a broader question: how much deference should courts give agencies when interpreting environmental laws like the ESA, versus stepping in to make their own judgements?

As of now, gray wolves are listed as endangered in 44 states, threatened in Minnesota, and managed by state agencies in Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, portions of eastern Oregon and Washington, and north-central Utah.

Written by Megan Smith, Living with Wolves.

Wolves of the West face ongoing challenges, from hunting pressures to habitat loss. Your support helps fund research, advocacy, coexistence, and educational conservation programs that give these iconic animals a chance to survive and thrive.