Wolf Species

The Gray Wolf

The Red Wolf

The Mexican Wolf (Grey Wolf subspecies)

The Arctic Wolf (Grey Wolf subspecies)

There are two species of wolves in North America:

There are two species of wolves in North America: the gray wolf (Canis lupus) and the red wolf (Canis rufus). The critically endangered red wolf is limited in its current range to a small portion of coastal North Carolina, but once roamed throughout the Southeast and much of the Eastern and South-central United States and north into Eastern Canada. With about 100 red wolves living in the wild, it is one of the world’s most endangered canids and is on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species. Scientists are divided over whether another wolf, known as the eastern wolf, is a separate species (Canis lycaon) or another gray wolf subspecies (Canis lupus lycaon).

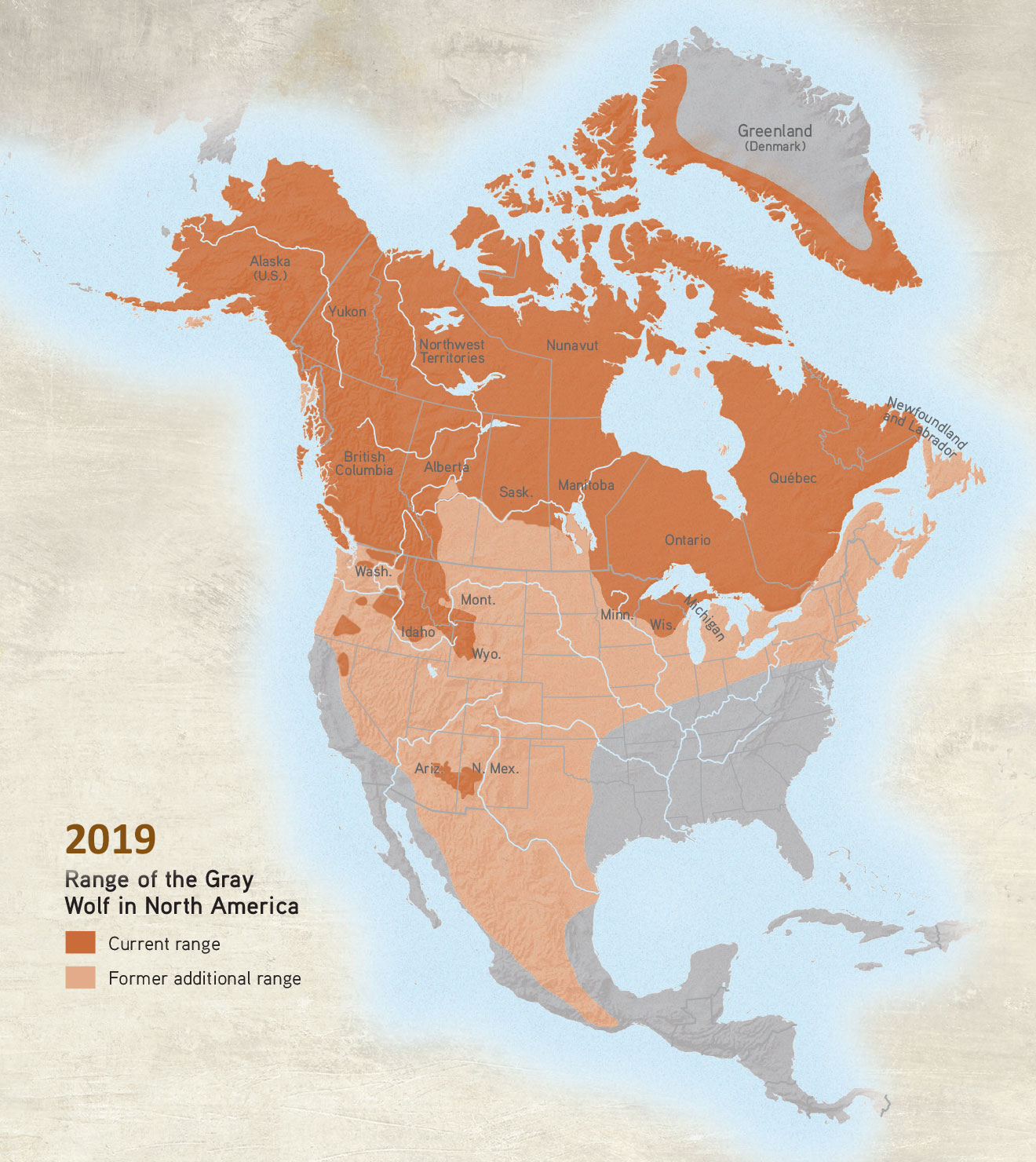

In North America, the gray wolf ranges across the U.S. Northern Rockies, the Pacific Northwest and the Western Great Lakes region, and from the U.S./Canadian border north to the Artic (including Alaska and Greenland) and in a small region along the Arizona-New Mexico border, with very few wolves struggling to survive in Mexico.

Beyond North America, the gray wolf ranges throughout northern latitudes inhabiting much of Eurasia, from Spain and Portugal to Scandinavia, the Alps and Eastern Europe and from the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent north across the former Soviet Union, China, and Mongolia. Gray wolves are residents of the world, and in many ways they are basically the same.

Subspecies

At one time, at least 24 subspecies of the wolf were recognized in North America, based on regional variations in overall size, color, and skull configuration. However, wolves travel great distances, which can result in interbreeding between subspecies often blurring the distinction between types. Common names such as eastern timber wolf and Rocky Mountain wolf describe geographic origin more than distinguishing physical characteristics. All gray wolves are much more similar than they are distinct.

Current classification divides North American gray wolves into four to six subspecies. The southernmost and smallest of these subspecies, the Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) is the most rare and critically endangered subspecies of gray wolf, with fewer than 100 animals surviving in Arizona, New Mexico and Mexico. The Mexican Wolf or “lobo” continues to receive federal Endangered Species protections, though they have been given the unfortunate designation of “Nonessential, Experimental.” This designation allows for what the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) refers to as “increased management flexibility.”

The Arctic wolf (Canis lupus arctos), resides in North America’s northernmost latitudes. Notwithstanding the debate over the eastern wolf, the other two subspecies currently recognized, which account for most of the wolves in the United States and Canada, are the Great Plains wolf (Canis lupus nubilis) and the Rocky Mountain Wolf (Canis lupus occidentalis).

What is a Pack

A Pack is a Family

Wolves are highly social animals that live in family groups, also referred to as packs. A family of wolves can consist of only parents and a few offspring, or it can be large and extended, including aunts and uncles, siblings, grandparents, and even adoptees.

The most basic form of a wolf pack consists of a bonded pair, known as the breeding pair or alphas. These are the leaders of the family and their bond can last a lifetime. The vast majority of the time, only the breeding pair within a pack reproduces. Breeding occurs early every year, in late winter. After a two-month or 63 day gestation period, pups are born underground in a den. The timing of this breeding cycle is such that pups are born at a time of year that will give them the best chance of survival with much of spring and all of summer and fall ahead of them to develop into nearly full grown wolves capable of surviving the next winter.

Pack size varies depending on geographic location and season, as well as prey size and availability. Small packs may consist of only two wolves, while larger packs can have more than twenty.

Physical Characteristics

An average-size North American male gray wolf weighs from 70 to 130 pounds, stands 26 to 36 inches at the shoulders, and stretches five to six feet from nose to the tip of the tail. Females are about 20 percent smaller. The smaller Mexican wolf weighs 50 to 80 pounds. The coat or fur of a gray wolf can be many shades of gray, tan, brown, rusty red, cream, buff, and solid black or white. Arctic gray wolves tend to be creamy white and blend in better in landscapes dominated by snow and ice.

The fur of a gray wolf consists of two layers: the outer guard hairs shed water and provide the markings, while the dense undercoat provides insulation. A wolf can curl up in the snow and sleep in temperatures of minus 50° Fahrenheit (minus 45° Celsius).

Wolves roam over large territories and are built for distance running. Their chest is narrow, which makes forging through deep snow easier. Their legs are long and closely set together at the front, so that the rear paws follow the front paws in the same track. Their paws are large, almost the size of an adult human hand, which allows for easier travel across snow and other terrain

As befits top-level carnivores, wolves have large teeth, and jaws with a bite force of 1,500 pounds per square inch, capable of crushing the thighbone of a moose.