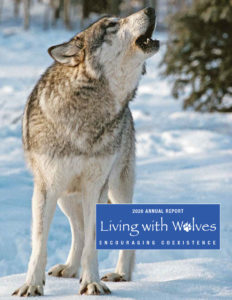

2020 Annual Report

2020 Annual Report

Dear Friends,

Whenever people come to know an animal over time, the animal’s unique characteristics and tendencies reveal themselves. As we gain insight into their individuality, a heightened sense of wonder and appreciation develops. Beyond our observations of the Sawtooth pack, we have

come to know a number of other extraordinary wolves through the wolf watchers in Yellowstone National Park. Wolf Number 253 is one such wolf who served as an ambassador for his species through his remarkable life.

His three-legged gait made him one of Yellowstone’s most easily recognizable wolves. By the time wolf spotters identified him as a juvenile, he had already sustained the injury that left him partially crippled. Everyone referred to him as Limpy or Hoppy. Limpy was born in 2000, a young member of the famous Druid Peak Pack. Wolf watchers admired his tenacity on the hunt, helping to take down elk without his

front right leg touching the ground.

In 2002, Limpy was struck with wanderlust, making his way 200 miles through Wyoming, all the way to Morgan, Utah. He may have been searching for a female wolf, or perhaps he was gripped simply by the desire to explore. Despite his injured foreleg, Limpy had an indomitable spirit. As one reporter said, “His heart seemed stronger than his legs.”

His stint as the first wolf in Utah in 70 years was short-lived. Ironically, one of his good legs found its way into a coyote trap. U.S. Fish and Wildlife officials collected and released him at the northern edge of Grand Teton National Park.

Limpy crossed the territories of several hostile wolf packs to return to his old home and birth pack. Back in Northern Yellowstone, he settled into the rank of beta wolf. Together, he and the famous alpha pair, 21 and 42, became known as the Druids’ “Big Three.”

There’s no exact count, but over his lifetime, Limpy must have covered well over a thousand miles. Even as he entered his eighth year, he was still given to wander. In the end, his spirit of exploration proved fatal.

In 2008, Limpy left his family and the protection of Yellowstone once more, and he headed south into Sublette County, Wyoming, where stores sell T-shirts depicting a wolf in crosshairs with the slogan “Smoke a Pack a Day.”

For his entire life, Limpy had been a stalwart deer and elk hunter. No matter how deep into cattle country he roamed, he never attacked livestock. From a ranching standpoint, Limpy was a model wolf, but someone shot him just the same.

Opponents of wolf recovery stoke fears over wolves’ insatiable hunger for livestock. The truth is, far fewer livestock animals die as a result of wolf predation than from storms, injury, or disease. But statistics don’t seem to matter to those who cling to the 19th-century mindset that the only good wolf is a dead wolf.

In Wyoming, people believe in the traditional values of the American West: bravery, independence, perseverance, and self-reliance. Yet we doubt that the hunter who shot Limpy realized that the creature he was about to kill was the embodiment of the very qualities he admired. If he had recognized an adventurous spirit, full of courage and curiosity, would he have pulled the trigger?

Limpy defied the odds for years. The death of a wolf known to many garners particular attention, but there are far more untold stories of the nameless. Therefore, we remain steadfast in our mission to improve the chances for wolves to exist in the remaining wilderness they deserve to call home.

Thank you sincerely for your ongoing support of Living with Wolves. Story excerpted from the Dutchers’ book,

The Wisdom of Wolves