The wolf is a keystone species. What does that mean?

Keystone species are animals that have a significant impact on the ecosystem despite relatively low population numbers. In the absence of keystone species, a dynamic ecosystem is often drastically altered and destabilized. Keystone animals are usually top predators fulfilling an essential role in predator-prey relationships. If the keystone species were to disappear from the ecosystem, no other species would be able to fill its precise ecological niche. Such disappearances (or removals) have dramatic radiating effects throughout the ecosystem.

In the Absence of Predators

So, what happened when people eliminated the vast majority of top predators from Yellowstone National Park in the early 1900s?

Elk are the primary prey of the park’s top predators: wolves, mountain lions and bears. With most of these predators removed, elk numbers rose, which triggered many other changes in the park. Elk became so numerous that their browsing prevented the new growth of many of Yellowstone’s “leafy” deciduous trees and shrubs. Aspens, cottonwoods, and willows, all of which have many important functions, contribute to the health of streams and rivers and provide ideal habitat for a wide range of aquatic life, including trout.

Rocky Mountain ecosystems can be quite dry, and the soil can become parched as the hot summer advances. During this time, water and aquatic habitat become increasingly vital. The same trees and shrubs that keep the streams deep, shaded, and cool, provide beavers with food and building materials for dams. Behind those dams, ponds act as a calm water sanctuary for an abundance of life above and below the water. The still water of these ponds and the moist soil that surrounds them act as secure nurseries for insects, amphibians, fish, ducks, muskrats and beavers. Many song birds nest in the lush vegetation and glean it for insects to eat. The deep water of beaver ponds also provides food and habitat for moose. Ponds and slow moving streams, especially in the heat of summer, keep the ground saturated, a necessity for many willow species that must have wet roots to survive. Beaver colonies can be extensive, and they provide myriad benefits.

Over the many decades that wolves and mountain lions were entirely absent from Yellowstone, and bear populations were much lower than they are today, massive numbers of elk wreaked havoc on these fragile ecosystems. The ecology of the park was dramatically altered and biodiversity reduced. Perhaps the most longstanding, damaging effect of their absence was the dropping of the water table in areas once kept lush by beaver colonies.

When Predators Return

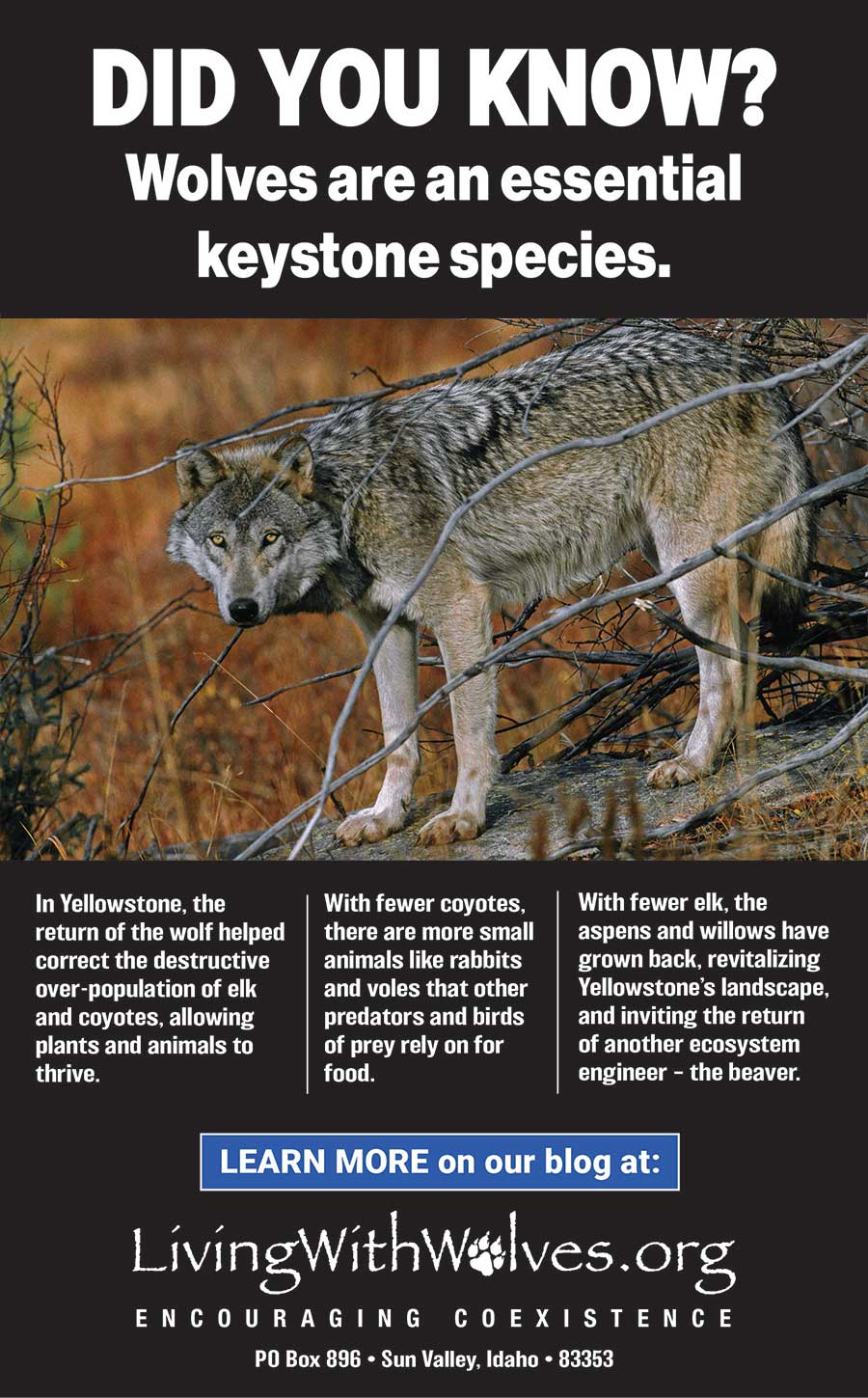

Wolves and mountain lions have returned and the bear population has increased considerably. With the renewed presence of these top predators in the park, the elk population has been reduced to a more ecologically sustainable level. With fewer elk browsing, there has been less pressure on specific types of vegetation especially in fragile riparian areas, allowing deciduous trees and shrubs to recover in many places.

Many new stands of aspens have emerged. However, thus far willow recovery has been more fragmented. In some areas, the willows have returned, leading to the welcome return of beavers. But where the groundwater has dropped beyond the reach of willow roots, those areas remain devoid of willows and beaver colonies. The recent pattern of more frequent droughts has also affected the groundwater and impedes the likelihood of willows returning to some areas. Perhaps beavers will find a way to slowly, dam by dam, reclaim the arid ground around some of Yellowstone’s once verdant streams. Time will tell.

The suppression of forest fires has also curtailed a vitally important cycle of death and rebirth. Fires burn overly congested mature forests while bringing critical nutrients and minerals to the soil. Where fires burn, aspens and grasslands often emerge, creating another important habitat.

Another consequence of removing the large predators from Yellowstone was the emergence of coyotes as the top predator, leading to other unforeseen consequences and impacting many species, especially those that rely on the grasslands ecosystem. Wolves directly compete with coyotes over territory, kills and carrion, and in other ways. In the absence of wolves, coyotes flourished at the expense of other mid-sized predators that prey on the same small rodents that thrive in grasslands. The return of wolves has thinned out the number of coyotes, resulting in more food for a host of animals, including many birds of prey, foxes, weasels and more. Even pronghorn have benefited from the return of wolves.

“No species is truly redundant because all contribute to an ecosystem’s ability to function efficiently…Although we don’t know why we need each species of chickadee or spider, we are likely to find out later, when it’s too late, why it’s wise to save all the pieces, including those.” Christina Eisenberg, Ph.D., Ecologist, Author, Living with Wolves Advisor

The short video “Yellowstone InDepth: The Northern Range” complements the information in this blog post. Follow the link above to the Gray Wolf page and scroll down to the section Changes in Their Prey.