It may seem a stretch that wolves could benefit trout. One lives in water, the other on land. How could their lives be interwoven? Scientific discoveries have shown that the presence of wolves and other predators leads to clear, deep and cool mountain streams lined with lush vegetation and beaver ponds. What connects wolves to water systems and to trout? Answers to these questions were found in Yellowstone National Park.

Yellowstone's Ecosystem: A Turbulent Past

The protective sanctuary of Yellowstone provides researchers one of the best opportunities in the world to study wolves and their influence on ecosystems. But that was not always the case. Wolves and other predators were not looked upon favorably in 1872, when Yellowstone was established.

By the mid-1920s, wolves were eradicated from the park. Mountain lions suffered a similar fate. Consequently, shortly after these predators of elk were eliminated from the park, elk populations ballooned. In short order, a burgeoning elk population was impacting critically important vegetation along streams and rivers, and creating an ecological problem.

For more than thirty years, the park service engaged in methods to control the elk population including shooting them or trapping and exporting them to other locations. Under pressure from congressmen and the hunting community, the park terminated their population control program, and the elk population once again exploded, to the detriment of the park’s ecosystem.

The Return of Large Carnivores

Mountain lions began a slow return to Yellowstone in the 1980s. Also, over the past several decades, there has been a substantial increase in the bear population. And with the recent reintroduction of wolves in the mid-1990s, scientists have been given the opportunity to observe a natural system before and after the restoration of its top carnivores.

The transformational influence of wolves appears to be especially prevalent in Yellowstone, where it has been meticulously documented. There are few other places in the world where the natural life of wolves remains largely unaffected by human impacts. Even today, after two and a half decades, there is no end in sight to the lessons being learned.

Expecting that elk would quickly become the wolves’ preferred food source, park managers anticipated that there would be some changes in elk behavior and numbers. What they did not anticipate was how much the changes would evolve, radiating throughout the park and revealing complex relationships that transcend far beyond elk and wolves, even reaching the park’s rivers, streams, ponds, beavers, insects and trout.

From Wolves to Trout

In the 70 years wolves were absent from the park, elk lived without a major threat of predation. This enabled them to take advantage of lush, streamside vegetation in a way that previously presented too much risk. The renewed presence of wolves kept elk moving such that they would eat a little and move on without over-browsing the vegetation.

Without pressure from wolves, elk will eat plants, like willows or cottonwood saplings, all the way to the ground. This often kills the plant or prevents any significant regrowth. When this happens to plants that are vital to stream hydrology, there are very notable consequences. In the absence of wolves, Yellowstone’s creeks and streams ran faster and became wider, shallower, murkier, and warmer. Consequently, what was once a fertile oasis of verdant riparian vegetation had become, in contrast, a biological desert.

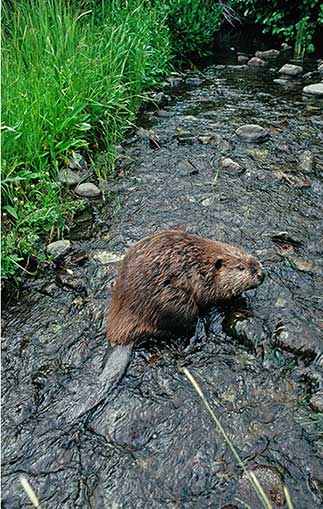

Streamside vegetation serves many purposes. It mitigates erosion, keeping streams deep, cool, clear, slow and meandering. The shade created by willows and cottonwoods also helps keep streams cool while providing habitat for songbirds and insects, as well as food and building materials for beavers. With the return of wolves came a revitalization of these riparian ecosystems, which is further elaborated in our blog on keystone animals.

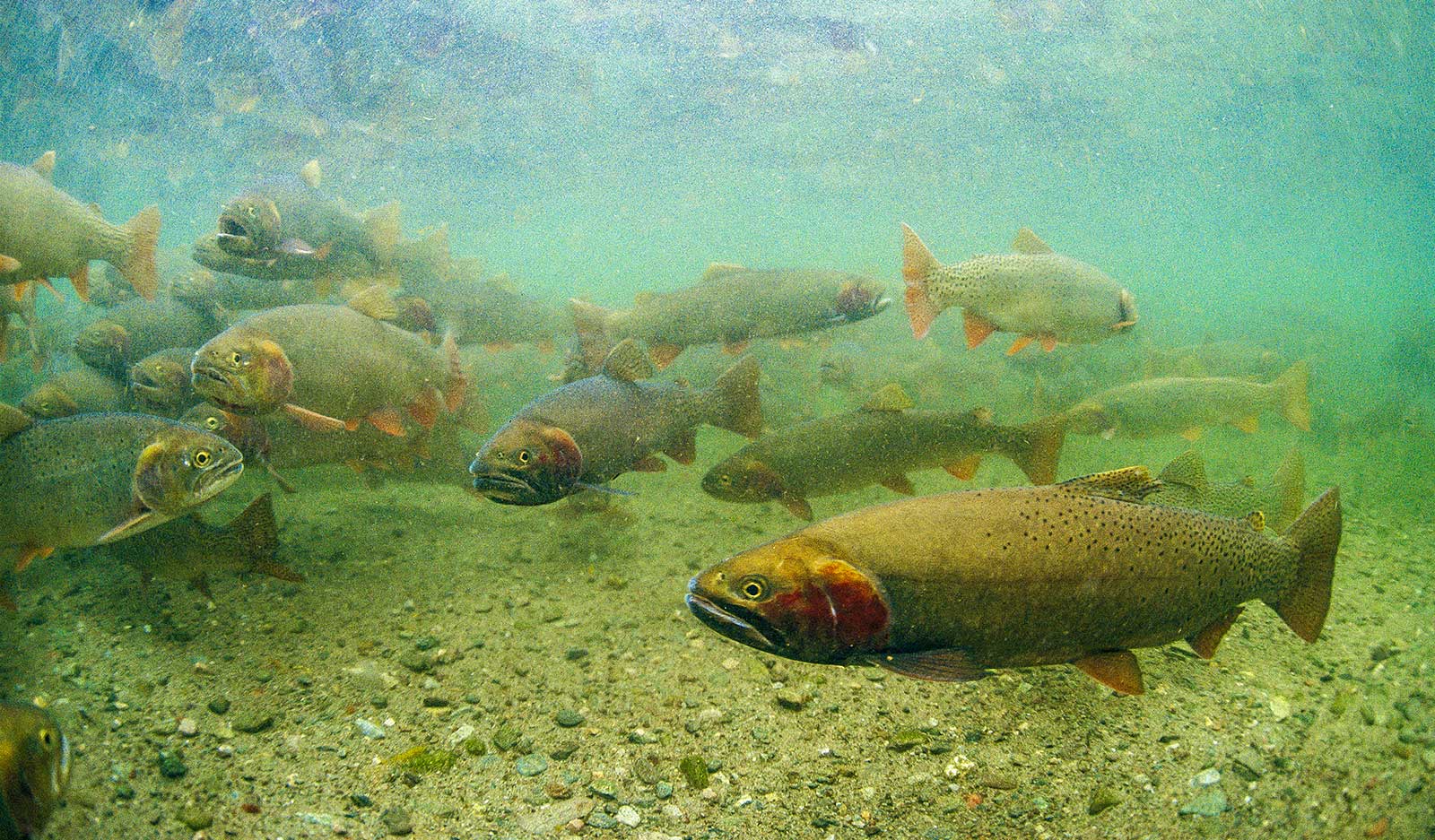

So, what does this have to do with trout? A Rocky Mountain stream in its natural condition, as well as the beaver ponds it invites and supports, is the ideal environment for the life cycles of many insect species, offering secure habitat for their larvae. Insects and their larvae make up a large part of the diet of trout and other freshwater fish species.

Even if some insect species are able to persevere and have a successful life cycle in fast, shallow and murky water, this is of little help to trout. Trout are sight-feeders. In all stages of an aquatic insect’s life, trout need to be able to see the insect in order to hunt it.

They feed on young swimming insects in the larval or nymph stage. Later, trout will feed on the larvae as they transform into fast moving pupae. When insects are getting ready to leave their aquatic nursery they are particularly vulnerable. In open water, often unsheltered by rocks and aquatic vegetation, undergoing another transformation, “emergers” rise toward the surface. Just below the surface they struggle to shed their old skin or exoskeleton, and if they successfully emerge as a winged adult without being eaten, they finally take to the air.

But it doesn’t end there. The aquatic insect’s life cycle draws it back to the water. If they aren’t prematurely blown to the surface of the water or knocked down by a rain drop, they must eventually return to the perilous surface to lay their eggs giving trout one final opportunity to capitalize on the many stages of the life of an insect.

Whether the insect is a larva, nymph, pupa, emerger or winged adult, trout need to see it to eat it. In fast-running, silty, murky water, unregulated by beaver dams and stream banks that are fortified by the roots of cottonwoods and willows, trout will struggle to find food and their numbers will decrease. They either starve or swim to more suitable habitat.

When a cow elk suddenly lifts her head from browsing on a willow, while standing on the bank of a stream, and a familiar but threatening scent, sight, sound, or simply some innate instinct persuades her to move on, that is the moment that connects wolves to trout. While it may not be easy to identify cause and effect within ecosystems, the relationship between wolves and trout is a great example of the interconnectedness and importance of all species.