You can see a lot of wolf in your dog.

We recognize the face, a broad mask that tapers into a long muzzle. We have looked into the eyes, bright with curiosity. We understand the messages conveyed through posture: the alertness in a cocked ear, the playfulness of a bow, the confidence and fear, both revealed by an expressive tail. We can be forgiven for thinking we already know the wolf, for in many ways we already do. We can see a lot of wolf in our dogs.

Genetics and Domestication

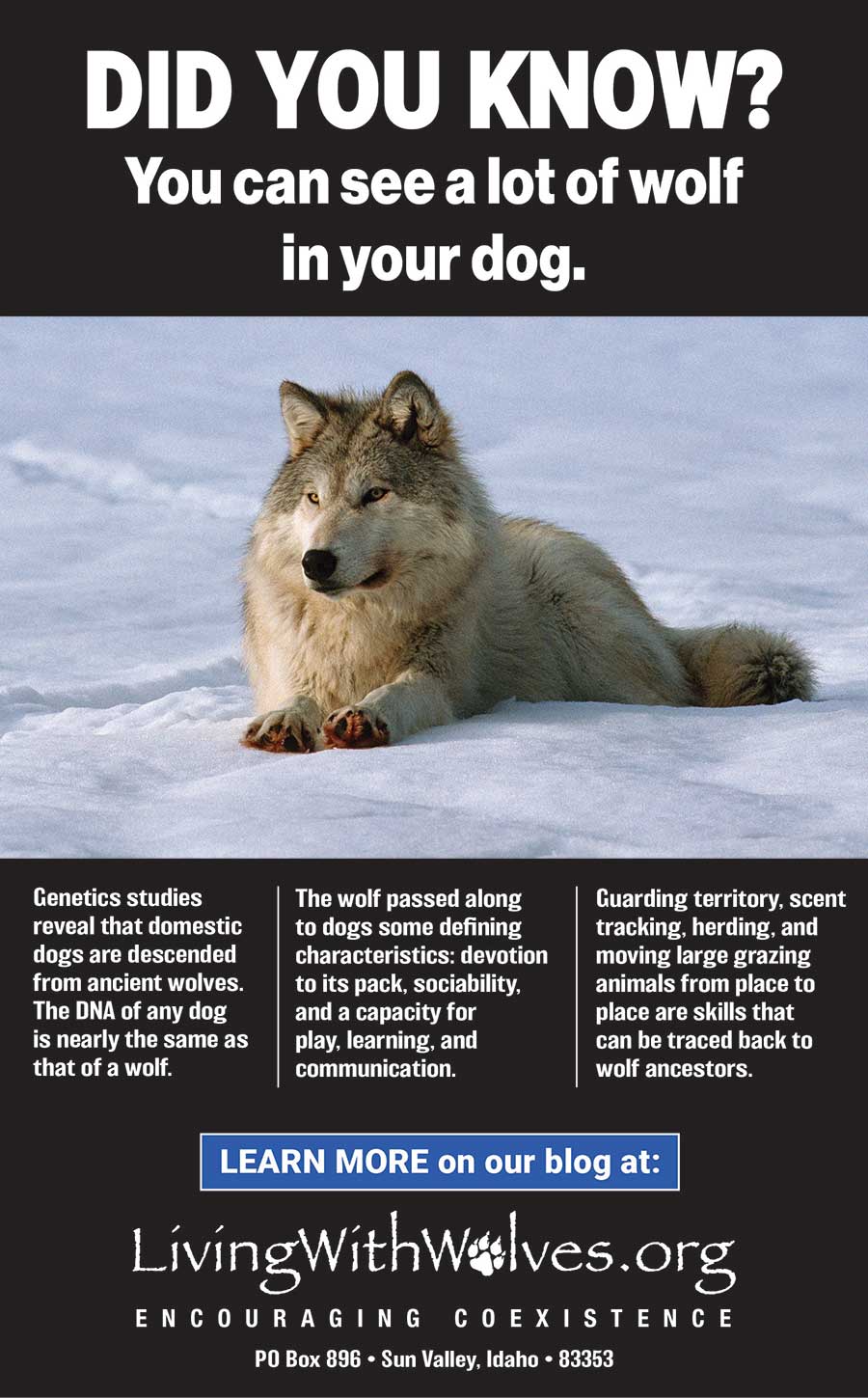

Genetics leaves little doubt that our canine companions are descended from prehistoric wolves. Before the advent of genomic sequencing, it was thought that dogs were the product of the domestication of various wild canines. But by sequencing and comparing the wolf and dog genomes, we now know that both dogs and the wolves of today share the same wolf ancestor, and that dogs did not originate from any other canine. There is also evidence that wolves and dogs continued to interbreed through the millennia.

Independent scholar and journalist Mark Derr has researched and written extensively on the relationship between people and dogs. He suggests that human domestication of dogs grew not from subjugation but from friendly interspecies socialization based on mutual benefit. He explains how humans and wolves may have first formed an early alliance, wherein each benefited from the strong suits of the other. Wolves, for example have a far superior sense of smell, which helps them detect and track prey.

“Wolves are adept trackers and skilled at holding their prey at bay. They are excellent long-range pursuers of game, but they are not the best closers on the planet,” writes Derr. Most of the time, wolves are unsuccessful on their hunts. Humans however, with their weapons, do make good closers, especially given the opportunities wolves could provide. Derr describes “opportunistic humans” learning to observe and follow wolves “to their potential prey and then stepping in for the coup de grâce.”

Social Tendencies and Unique Qualities

We share another essential ingredient with wolves that would have enabled our species coming together. We are both highly social. Derr explains, “Whatever the circumstances of their meeting, wolf packs and groups of human hunters and gatherers were remarkably similar—extended families devoted to raising and educating their young cooperatively to fit into their society; protecting their homes and each other.”

Animals that live in social groups tend to be sociable. Wolves and people are both sociable with our own kind, but how did wolves and people become sociable with each other? In sharing a mutual interest, we learned to cooperate. Our cooperation likely improved as we learned each other’s patterns and anticipated the other’s intentions. Certainly when people overcome challenges by working together, they can develop a bond. It isn’t difficult to imagine that as we shared in the struggle to survive, humans and wolves would have had the chance to bond.

Given the strong loving bonds we share with our dog companions, it is not surprising that growing archaeological evidence suggests that humans befriended wolves long before we domesticated them. While we are not sure exactly how it happened, the domestication of wolves was clearly to our benefit.

The traits that wolves passed on to dogs served us well as we became shepherds and farmers. We capitalized on the wolf’s territorialism to create a dog that steadfastly guarded our flocks and property. We put the wolf’s superior sense of smell and knack for locating prey to use as trackers and retrievers on our own hunts. We transformed the wolf’s skill at harassing and maneuvering big grazing animals into a herding instinct, helping us move our livestock.

The wolf also passed along its most indispensable qualities: devotion to its pack, sociability, and a capacity for learning, communication, and expression. In turning the wolf into the dog, we created the ultimate companion, a faithful friend that can understand our intentions.